Originally posted by DAMNTHEWEATHER

View Post

Great Brunswick Street grew increasingly commercial during the 19th century, with offices, builders’ yards, mechanical and electrical suppliers and other forms of light industry emerging.

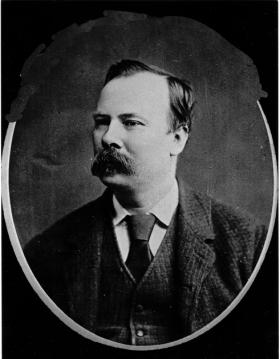

It was within this context that James Henry Pearse, father of Padraig Pearse, established his monumental sculpting business at Number 27 in 1870, having previously operated a sculpting partnership at Number 182. Following his death in 1900, the business was carried on for a few years under the Pearse & Sons name by his younger son, sculptor William Pearse (1881-1916), with some help from his more famous elder son, Patrick Pearse (1879-1916).

It was within this context that James Henry Pearse, father of Padraig Pearse, established his monumental sculpting business at Number 27 in 1870, having previously operated a sculpting partnership at Number 182. Following his death in 1900, the business was carried on for a few years under the Pearse & Sons name by his younger son, sculptor William Pearse (1881-1916), with some help from his more famous elder son, Patrick Pearse (1879-1916).

Comment